flawless ƨƨɘlwɒlʇ

Internet Janitor

Creator of

Recent community posts

Puppeteer includes a simple screenshake effect. If you're using that library already, you can just include the !shake command in your dialog scripts like in the example. Here's a simplified version of how that works internally that could be used elsewhere- adjusting "shake_mag" and the duration of the transition (here 15) can tune how the effect looks:

go[card on shake_trans c a b t do local shake_mag:30,30 local m:shake_mag*1-t c.pattern:1 c.rect[0,0 c.size] c.paste[a (random@2*m)-m] end 15]

Unfortunately, supporting non-Latin-alphabet languages in Decker is not straightforward. Phinxel has a few suggestions for workarounds, but any way you slice it a great deal of work would be involved.

To hide Decker's main menu, you'll need to lock the deck. (The following page describes how you can save a "protected" copy of the current deck.) Whether you're exporting a protected copy of a deck or using the ordinary save menu, all you need to do to create a web-playable version of a deck is save with an ".html" extension.

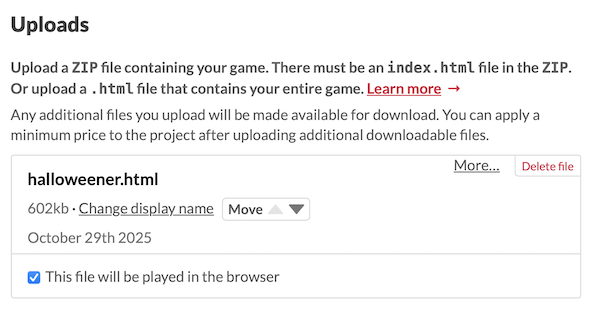

When you create your project page on Itch.io, upload the .html file you saved, and mark it as "played in browser". It'll look something like this:

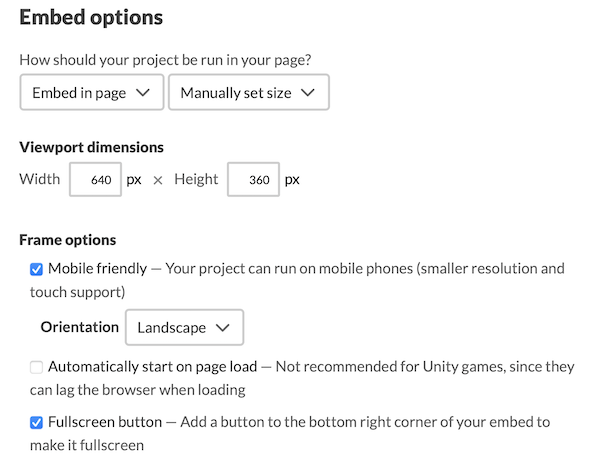

There are also additional settings to configure how your game will be embedded in the web page:

The defaults are mostly fine, but I recommend enabling the "fullscreen button" for most projects.

In K, you'd solve this kind of problem with the "where" (&) operator:

&0 1 0 0 1 1 4 *&0 1 0 0 1 1

Lil doesn't have an independent monadic primitive for this operation; it's folded into the query language:

first extract value where 0=map@value from np

This is a little bulky when you're doing something simple.

When you only need a single result, you could consider forming a dictionary:

((0=map@np)dict np)[1]

It's also possible to perform an equivalent "masking" operation just with arithmetic:

m:0,0,0,1,0 # "one-hot" boolean vector m*keys m # (0,0,0,3,0) sum m*keys m # 3

In Lil, dot-indexing with an identifier and bracket-indexing with a string are equivalent:

card.parent.event.moving card.parent.event["moving"] card.parent["event"]["moving"] card["parent"]["event"]["moving"]

This is a very convenient shorthand when functions take a single string as their argument, but I can see how it might leave you puzzled about passing extra arguments to the "event" method of deck-parts. You're looking for something like:

card.parent.event["moving" which.text]

Make sense?

Given a list,

x:("A","B","C","D")

There are several ways we could find the index of a specific element.

Building a dictionary:

(x dict keys x)["C"]

Querying:

first extract index where value="C" from x

Arithmetic:

sum (keys x) * x="C"

Variants of these methods can also be used to search for several items in parallel:

(x dict keys x) @ "C","A" # (2,0) extract index where value in "C","A" from x # (0,2) extract index where value="C" from "ABCBABBCC" # (2,7,8)

If you're ever specifically searching within strings, consider rtext.find[] (which can optionally ignore case, too).

first @ rtext.find["ALPHABETICAL APPLES" "A"] # (0,4,10,13)

The background image of a card is "card.image", an Image Interface. You can do some kinds of drawing and compositing directly with an Image, but it is less general than a Canvas Interface. Images are simple values which can be created on the fly, while Canvases are widgets that are attached to a deck and have awareness of e.g. the deck's palette, brushes, and fonts.

You could make a canvas the size of an entire card, if you like, and/or draw to a canvas elsewhere and use .copy[] and .paste[] to transfer image data to the card background.

Lil variables are mutable; Lil primitive datatypes (numbers, strings, lists, dictionaries, tables) are immutable. Decker provides several "interface" types which can represent mutable data structures: Array, Image, Sound, and (much more flexibly in the v1.64 Decker release than in v1.63 and earlier) KeyStore.

Within the Decker environment, most closures only live as long as a single event, though "blocking"/synchronous scripts could persist for many frames.

There is no built-in mechanism for serializing a function along with its captured closure, so you can't e.g. stash a callback for later in a field's .data attribute. None of Decker's APIs are designed around callbacks for this reason; we instead send events to deck-parts like widgets or cards.

Modules have closures which persist as long as a deck is open and their script isn't modified, so in principle they offer opportunities for weird and fanciful (ab)uses of mutable closure.

And of course, in Lil scripts run with Lilt, outside the Decker environment, the world is your oyster.

I'm sure many of us have encountered Neko from time to time during our computing adventures. I spent a little time tinkering, and whipped up a version of this iconic pixelated companion for Decker:

If you want this little scamp in your decks, you can copy and paste it from here: http://beyondloom.com/decker/goofs/deko.html

This contraption uses Kenji Gotoh's Neko sprites, as is traditional. If any of you are feeling like some adventure, it's a simple matter to edit the frames stored in the internal "sprites" field to customize your Deko. Perhaps you could add new behaviors, more interactivity, or sounds? Feel free to share your variations or ask question!

I've made some clarifications to that table to be more precise.

Primitive widgets will ONLY be sent automatic view[] events when they are set to be "animated" AND the card upon which they appear is the active card.

Before the .animated property existed, a cruder way of obtaining a 60hz event pump was to go[] to the current card without any transition effects, indirectly scheduling the view[] event for the card to be re-triggered. One advantage of this old approach- which still works fine- is that by making the "dispatch plumbing" within a card explicit, it's very easy for blocking scripts to send their own "synthetic"view[] events to the current card and keep everything ticking along in the background. Dialogizer provides a synthetic animate[] event while its blocking dialogs are open that can be forwarded to view[] if desired.

I don't think the load time is too bad at 20mb; it's noticeable, but compared to games made in Unity or Ren'Py loading in a few seconds is still pretty fast.

Looks like you built this game with Decker 1.62; in the 1.63 release I fixed a bottleneck that was slowing down deck loading a bit in native-decker, but it was most noticeable in debug builds. Still, upgrading might make your development a little bit snappier. I'm tinkering with some other performance improvements presently.

Using contraptions as reusable graphical assets is certainly one way to cut down on repeated background images; it looks like you're doing this pretty extensively already for puzzle elements. If any elements are one-offs you could also use canvas widgets as graphical elements you can show/hide, move around the card, or copy from place to place. I was a little surprised to see that you aren't using canvases at all in this deck!

The macFieldWindow contraption is designed for displaying "rich text", which can contain hyperlinks, inline images, and text spans with customized patterns or fonts, but cannot contain arbitrary embedded widgets, like a button. It would be possible to add buttons to the contraption by editing it, but I recommend sidestepping that route for now if possible.

I'm not clear on what you mean by "the font importer". In this tutorial post I describe steps one could follow for building a special-purpose tool for converting bitmaps of glyphs from a particular font collection into Decker fonts, but it makes a variety of simplifying assumptions: assuming glyphs are a particular size, that they appear in ASCII order, that the imported image is a black-on-transparent image that's already completely ready to use, and so on. The image you posted contains antialiased white-on-transparent glyphs; you'll have a much easier time importing and editing them as black-on-white or black-on-transparent, and they will need to be flattened into 1-bit color.

If you have a set of glyphs as an image, a somewhat more general approach to building a font from them would be to use the Font Editor that comes with Decker (examples/fonts.deck) and which I linked previously. The "sheet" mode of this tool is designed to break the card background image into uniform-sized glyphs based on the boundaries designated by the invisible button named "workzone". The grid overlay and "snap to grid" mode can make it easier to select and reposition glyphs within this tool so that Decker will understand which DeckRoman character they each correspond to. You'll need to make sure your new font's glyph size is set properly and that "workzone" is positioned to enclose all the glyphs before you can "Apply" your changes to the sheet, and if you don't want a monospaced font you'll probably need to make additional refinements to each glyph's sizing in the "glyph" tab.

1. Decker supports a limited set of unicode characters within text, and unrecognized characters are turned into character 255, "UNKNOWN", upon ingestion. You can, however, very easily customize how this character appears in a given font using the font editor. (The font editor is part of a larger deck All About Fonts that contains a variety of other notes you might find useful).

2. It isn't possible to use a different font within a field exclusively while text is highlighted, but you could certainly make intentionally illegible custom fonts that could still be copied to the clipboard as ordinary text. This would be mechanically a bit different, but might still preserve a similar idea. Perhaps there could be some affordance within the game for giving a player a "scratchpad" field they can paste into? You could alternatively build a contraption of some kind which encapsulates swapping out the font of a field when it is clicked, but it would be difficult to provide this kind of behavior on a granular level and still permit selection. In a locked field, links could be used to trigger arbitrary scripts when particular text fragments are clicked, but they do have a recognizable visual appearance: a dotted underline.

3. You cannot select text within a locked field, but there are a few subtle consequences of how field and text patterns work which might allow you to accomplish something similar to what you're describing:

- A transparent field on top of a black background (with text in the default pattern 1) will appear to be invisible until it is selected, in which case it will appear white.

- If you change the pattern of a span of text within a "rich text" field to white (rather than changing the default pattern for the entire field), it will appear to be invisible until it is selected, in which case it will appear white within a black selection highlight.

As a general note, some of the limitations of text and selections within Decker are a consequence of its approach to ensuring that fields are usable on keyboardless devices like tablets. The "touch input" mode (which can be manually enabled via the Decker menu) will interfere with some kinds of nasty text obfuscation tricks.

It absolutely is not. I have only published WigglyPaint here (on itch.io) and on newgrounds.com. If you see people sharing links to pirate sites, please ask them to link to this page on itch.io instead. Pirate sites may harbor malware or ads, and are frequently outdated and encrusted with misleading slop.

You might find it useful to take a look at lildoc.lil in the Decker repository. It's a markdown processor and Lil syntax highlighter used for generating all of Decker's documentation.

Depends on what you want, I suppose?

Out of the box, with no extensions or scripting, Decker is already a perfectly serviceable presentation tool: make slides as cards, put text in fields, doodle on card backgrounds, flip through them with arrow keys.

The included PDF module offers a starting point for making slide-decks capable of exporting printable thumbnail versions of themselves.

If you wanted slides to have rigid "templates" and a centralized way of altering or applying these styles across a large deck, you could consider making a series of full-card-sized contraptions- a contraption for title cards, a contraption for bulleted lists with a heading, etc- and placing one contraption instance on each slide.

It would also certainly be possible to write a lilt script that "compiled" a textual syntax like Adelie into decks, or perhaps a module that interpreted them on the fly.

The dialog boxes controlled by dialogizer are canvas widgets located on a specific card. You shouldn't go[] to a different card while a dialog box is open. There are plenty of other ways to hide a transition if you're really insistent, like hiding and showing other widgets on the current card or even using the sledgehammer approach and replacing the background image of the current card with a screenshot of a different one:

card.image.paste[app.render[someOtherCard]]

(Note that this will destroy any previous background image on the current card!)

Parsing "sys.now" into time-parts like your example:

p:"%p" parse "%e" format sys.now

Gives us a dictionary like so:

{"year":2025,"month":12,"day":18,"hour":23,"minute":30,"second":45}

Note that this time is in GMT. The hour (and possibly minute) values might need to be adjusted to reflect a time zone offset to get local time. Otherwise, people in certain countries might find the game much harder than others!

At any rate, we'll want to structure our checks from most to least specific. First, the easter-egg time. We want both p.hour to be equal to 12 AND p.minute to be equal to 13:

(p.hour=12)&(p.minute=13)

Parentheses are important here: remember that arithmetic precedence in Lil is right-to-left unless otherwise grouped by parentheses or brackets.

Since seconds range between 0 and 59, 7 appears in the seconds place iff p.second modulo 10 is equal to 7:

(7=10%p.second)

For your hour ranges, you'll probably need ">" and "<"; there are many ways to express the same thing:

(p.hour<10) | (p.hour>19) ! (p.hour >9) & (p.hour<20) ! p.hour in (10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19)

Bringing it all together, here's one possible approach for what you described:

if (p.hour=12)&(p.minute=13) # easter egg... elseif (p.hour<10) | (p.hour>19) | (7=10%p.second) # allowed... else # denied... end

Does that make sense?

The "+" operator in Lil is exclusively for addition. It will coerce strings into numbers in a best-effort fashion, which is why you're getting zero:

"5"+3 # 8 " 2.3" + "1Hello" # 3.3 0+"Hello" # 0

The "fuse" operator is binary; it expects a left string argument to intercalate between elements of a right list argument:

":" fuse "A","B","C" # "A:B:C" "" fuse "A","B","C" # "ABC"

Assigning a list to a field's ".text" attribute will implicitly concatenate the elements of a list together, as a convenience. The following are equivalent:

hellotext.text:"" fuse "Hi","There" hellotext.text: "Hi","There"

Cards are normally in scope by name, so you don't typically need a fully-qualified path to reach a widget on another card. The following will be equivalent from a card/widget level script:

deck.cards.A.widgets.name.text

A.widgets.name.text

Does that help?

If you aren't already, I strongly recommend using The Listener to try expressions out piece-by-piece as you develop.

Many of the requirements in this manifesto seem strongly oriented toward a statically-compiled system with a complex backend, but Decker does check a number of boxes:

- We don't need hot-reloads or live "previews"; everything in Decker is continuously interpreted on the fly. Likewise, we don't really have any concept of a "deployment" lifecycle apart from occasionally exporting .html builds of decks.

- Decks are single self-contained files which are, nevertheless, line-oriented, so you can dump them in the moral equivalent of a dropbox and get "atomic" updates or use a traditional VCS like git to manage changes.

- Using lilt to perform "headless" automated testing with the same scripting APIs as ordinary interactive Decker offers pretty handy facilities for testing. It's certainly possible to rig up test fixtures to run continuously as a deck is updated, but it isn't a default.

I wrote a new blog post outlining a number of useful design patterns and ways of working that fall out of the “stack-of-cards” metaphor shared by Decker and HyperCard:

http://beyondloom.com/blog/sketchpad.html

I'd love to hear your thoughts!

Most of the time, the fields and other widgets on different cards of a deck contain entirely different data. Occasionally though, as in this question, you might have data like a game's score counter that you want to display on and modify from many cards. There's an elegant way to (ab)use Prototypes and Contraptions to create this kind of "singleton" widget state:

When the value of a field in a Contraption instance has never been modified, the value of the corresponding field in the Contraption's Prototype is inherited. By exposing a ".value" attribute for our Contraptions which read from and write to a field in the Prototype, rather than the Contraption instance, every instance of the Contraption will share a single value:

on get_value do card.def.widgets.f.data end on set_value x do card.def.widgets.f.data:x end

This becomes slightly more complicated if we want the field to be unlocked and user-editable, since we can no longer rely on inheriting the prototype's value automatically. In this case, we will need to explicitly replicate changes back to the prototype and poll the value from the prototype when the contraption is updated by a view[] event:

on get_value do card.def.widgets.f.data end on set_value x do card.def.widgets.f.data:x end on change do set_value[f.data] end on view do f.data:get_value[] end

As a complete example, here's a "scoreCounter" prototype which uses this mechanism:

%%WGT0{"w":[{"name":"sc","type":"contraption","size":[100,20],"pos":[302,95],"def":"scoreCounter","widgets":{"f":{}}}],"d":{"scoreCounter":{"name":"scoreCounter","size":[100,20],"margin":[0,0,0,0],"description":"an example of a \"singleton\" contraption which shares data across every instance.","script":"on get_value do card.def.widgets.f.data end\non set_value x do card.def.widgets.f.data:x end\non change do set_value[f.data] end\non view do f.data:get_value[] end\n","attributes":{"name":["value"],"label":["Value"],"type":["number"]},"widgets":{"f":{"type":"field","size":[100,20],"pos":[0,0],"style":"plain","align":"center","value":"0"}}}}}

Anywhere a scoreCounter appears within a deck, it will represent an identical view of the same underlying value. A pleasant side-effect of this approach is that scripts on cards can refer to any scoreCounter when they want to read or modify the game's score; there's no need to reach for a "source of truth" on some specific card.

I hope some of you find this to be a useful technique for your projects!

If you want to increment a local variable, like "t" in your example, you must use the assignment operator ":" (read aloud "becomes" or "gets") like so:

t:t+1

Local variables exist only within the lifespan of a single event.

Persistent state, like an inventory or a system for tracking a user's action, must reside in a widget somewhere. This has been discussed many times and places within this forum. I recommend starting with this thread: https://itch.io/t/2702720/how-to-have-interaction-between-cards

By default, the Ply renderer doesn't have the deck, cards, or any local widgets in scope when it evaluates a Lil fragment, so it can't manipulate parts of the deck.

If you're using "twee.render[story passagename vars]" directly like in this demo, "vars" can be a dictionary containing arbitrary bindings, including references to the widgets of the current card.

The PlyPlayer contraption has similar functionality, but it is less flexible; you can read and write its .vars attribute, but this feature is only designed to store data that can be serialized in a field's .data attribute, not references to deck parts.

The easiest way to have Ply stories interact with a surrounding deck is to use the passage[] event that the PlyPlayer emits every time it visits a new passage. By keeping deck-influencing logic separate from the Ply story itself the story will still be entirely playable within the Twine editor. There's some relevant discussion in this thread.

Does that help at all?

Fun little update for PublicTransit- I added 8 new transition effects:

- RotateDown, RotateUp, RotateLeft, RotateRight: a variation on the "stretch" family with a different feel.

- PageDown, PageUp, PageLeft, PageRight: simulated 'page flip' effect to make your deck feel more like a book or pamphlet.

Itch.io GIF uploads have been busted for quite a while, so no preview GIF; just follow the link above, give them a spin, and see if any stir some inspiration in you!

Just to be clear, a field's .value attribute, which is represented as a rich text table, is the complete, underlying contents stored in the field. Fields have .text, .images, and .data attributes which can be read and written, but all three are alternate views/subsets of the same contents (as a plain-text string, as a list of inline images, and as encoded/decoded LOVE data, respectively), as scripting conveniences.

Buttons have a .value attribute as well, but it represents the boolean (1/0) value of checkboxes, and has no relationship to the .text attribute of the button, which controls the button's label.

Sliders have a .value attribute which corresponds to their numerical value, and Grids have a .value attribute which corresponds to the table data they contain.

From the reference manual's description of the Prototype Interface,

when a definition is updated, thename,pos,show,locked,animated,volatile,font,pattern, andscriptattributes of Contraptions will be preserved, as well thevalue,scroll,row,col, and image content of the widgets they contain (as applicable) if they have been modified from their original values in the prototype, but everything else will be regenerated from the definition. The state of contraptions is kept, and the behavior and appearance is changed.

Any other state that you wish to survive prototype modification should be stashed in internal widgets; I recommend refreshing these settings (alongside applying settings from the enclosing contraption instance like .font and .locked, where appropriate) in the view[] event handler in the prototype script.