DEMO available here: https://yozhikisblue.itch.io/the-inverted-spire

Hello everyone!

If you're anything like us, you've probably played many narrative-based games promising choices that really matter, and found yourself occasionally frustrated by the options that are actually available.

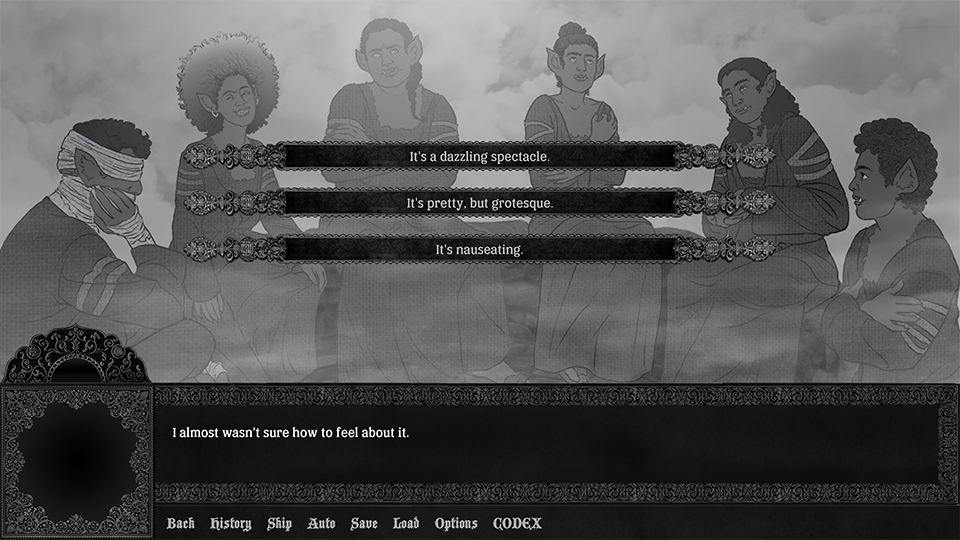

Sometimes the choice you'd like to make out of sheer practicality or personal preference simply isn't there. Other times, the existing choices can feel stifling because you're trapped between pure-hearted, heroic altruism and moustache-twirling evil.

So what makes a game where choices are diverse and fulfilling?

What makes a game where choices feel like they matter every time?

With our first official dev log on The Inverted Spire, we'd like to dive deep into what we really mean when we say our story offers meaningful choices.

Don’t worry, this entry won’t be containing any spoilers! (though you may be able to discern a little more about the direction of the story if you read closely)

To begin with, I would like to assure you that in The Inverted Spire, there are no purely “good” or purely “evil” routes in the traditional sense. This is not to say that you will not be making moral decisions, so much as those decisions will always be complicated by context.

It will not always be clear which is the kinder choice. Factors such as group morale, mutual trust, self-preservation and even the impact on relationships with individual characters make every choice a balancing act.

Rest easy that you will not instantly die or reach a “bad end” based on a single decision. You may, however, damage the trust of individual characters in ways that will have severe consequences later in the story.

All options are weighted to give the player the maximum possible maneuverability in their role as the player character.

The protagonist will rationalize any choice the player makes. Even choosing non-interference can have consequences just as, if not more interesting than injecting yourself into every conversation. Similarly, choosing to read, and in some cases, alter the minds of other characters can have a variety of unexpected and cumulative results.

Every decision you make in the Inverted Spire has a combination of the following consequences:

1. It will change the immediate response of the characters around you.

This isn't just a matter of one or two throwaway lines. Entire dialogue sequences leading into the next decision point differ significantly from one choice to another.

2. It will change how the protagonist’s personality is perceived by others.

All choices are weighted on their degree of “dissidence” and “compliance” according to the State of New Order citizen reputation algorithm.

All of the characters in The Inverted Spire were raised with “the equation”, and know it implicitly. Assertiveness and standoffishness will be noted, as will attempts to build mutual trust or sow discord. Patriotic and rebellious sentiments towards New Order will also be remembered in equal measure.

Other characters in the Inverted Spire all have different perspectives on New Order and their own idiosyncratic approach to life. Those who are more closely aligned with your choices may be more likely to trust you. You will also find it easier to read like-minded characters, and may notice details about their behaviour that would otherwise pass you by.

Sticking to expressing a particular set of views or a particular approach in dialogue can open up more extreme options in the same camp. Alternatively, changing your behaviour over time or choosing to act in a way that other members of the cast may perceive as out-of-character can have unexpected results.

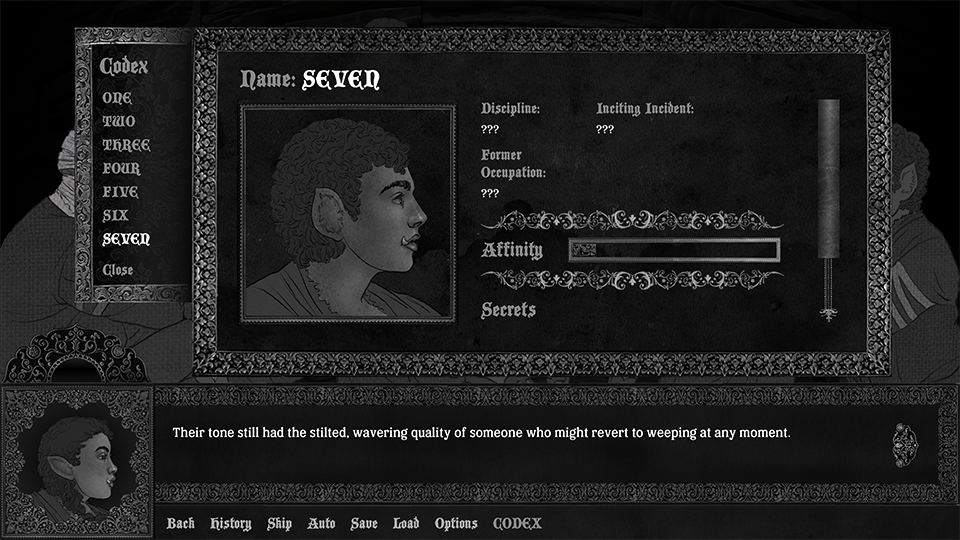

3. It will alter the protagonist’s affinity for individual characters.

Some actions and responses will have a more pronounced impact than others. For instance, mentioning a topic that sparks another character’s interest is not weighted as heavily as declaring that you think they’re lying, or revealing their secrets before the rest of the group.

*(Note that revealing secrets will not always have a negative impact depending on the context, and some characters may genuinely appreciate having their opinions questioned.)

Affinity will also affect how individual characters respond to your choices. Low affinity characters will put less trust in the protagonist’s words, and are less likely to support their claims. They may even challenge the protagonist directly.

In some cases, the protagonist will express themselves differently (and their words will land differently) depending on their affinity. For example, attempting to reassure a character with low affinity may not have the desired effect. Similarly, the minds of low affinity characters will be more difficult to read and alter.

High affinity characters may spontaneously come to the protagonist’s aid, seek out your support, or try to involve you in their schemes. Depending on the player’s approach, they may even open up about their past lives, develop a strong sense of camaraderie with you, or express romantic interest over time.

4. It will have delayed consequences for the direction the story takes and the choices that are available to you.

Not all consequences of your actions are immediately visible.

Having access to a key piece of information may completely change your perspective on a character, and offer new options in response to their claims.

Choosing to trust another character may leave the protagonist blind to their shortcomings. This can lead to disastrous results, but it may also earn you an ally when you need them most.

Your choices may also have cumulative results for how the characters interact with one another. For instance, provoking a character into a state of extreme anger may cause the rest of the group to grow more wary of them. It may also backfire, depending on your relative affinities, and cause the group to turn on you instead.

To give a more visual demonstration, let’s have a look at what a decision point looks like in-game:

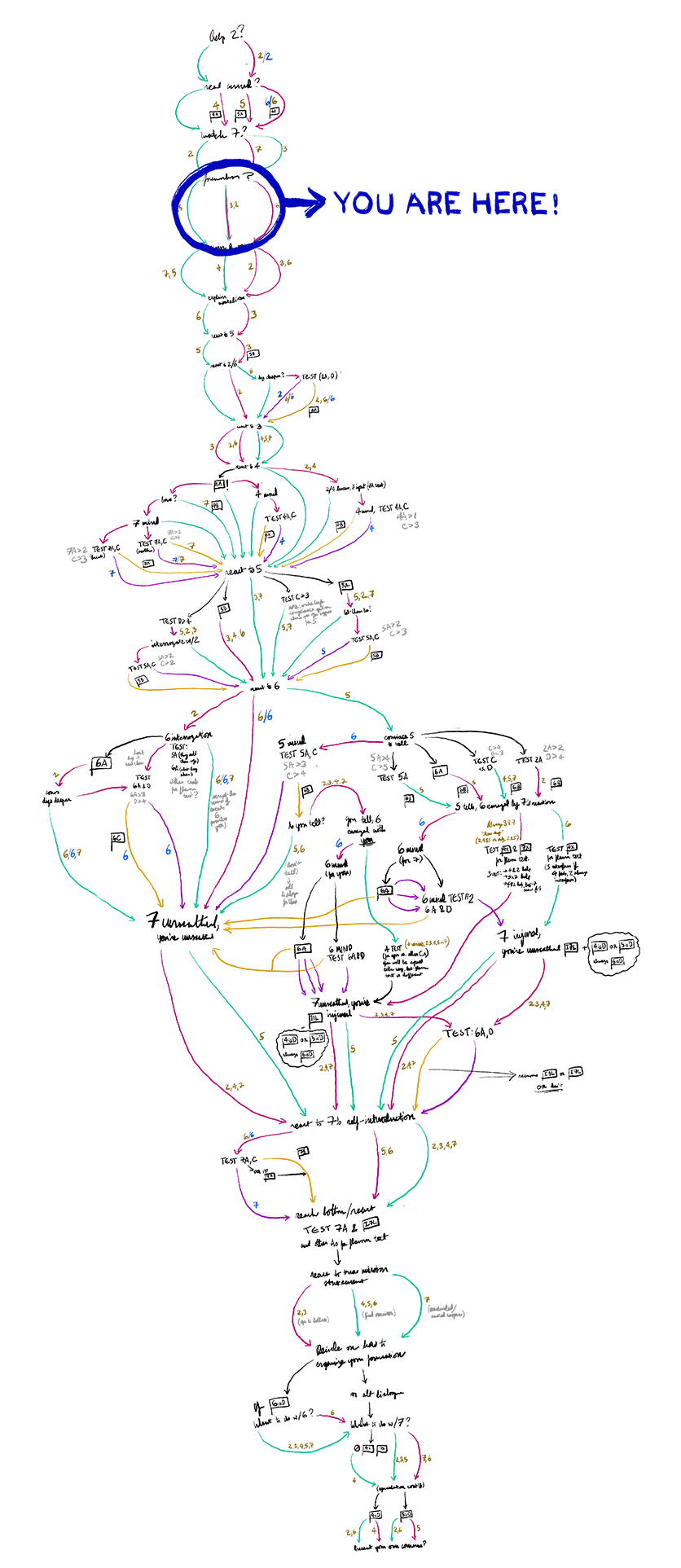

And compare that with what it looks like in the overall branching structure of a single chapter:

As you can see, the options also return to recurring narrative “anchor points.” These are either events or moments of self-reflection that transpire regardless of player choices. Anchor points keep the branching structure of our story manageable from the developer perspective. They also maintain narrative cohesion from a storytelling perspective.

The above example is taken from an early-development model for Chapter One to keep spoilers to a minimum. Its structure is made possible by the entire cast being kept together in a single place during their introductions.

Later chapters have an additional feature that will be familiar to VN fans- the narrative branches off depending on your character affinities, causing anchor points to become increasingly more dispersed.

As experienced developers coming from a web and learning software background, we are very cautious of the possibility of “feature creep”. Keeping the story as open-ended as possible without creating an insurmountable workload for our small indie dev duo is always a delicate balancing act.

This is also where you can help!

Making sure choices are meaningful and well-balanced is one of our highest priorities in creating The Inverted Spire. We will be relying on playtesters and individual player feedback throughout development to make sure we are producing consistently interesting choices with engaging results.

This means your feedback on story content between individual chapters is always appreciated!

We may not be able to follow up on every suggestion we receive, but will absolutely be listening to community feedback on what will make The Inverted Spire the most captivating story that it can be. ~<3