This post is very late to the party.

That's fine, by the way, I don't mind being a bit late to the party as long as I have something to say, it's just, I want to acknowledge that at the outset. If you're tired of this party, feel free to move on. The party is the question about why tabletop RPGs have rules. The modern iteration of this argument was arguably jumpstarted by "the rules elide blog post," here, carried forward in various niche blogs and discord server rants and youtube videos.

My take here is fundamentally that rules elide is wrong, or at least substantially incomplete, for what that's worth. To get there, though, we need to go way further back (or, perhaps, beyond) in discourse and summon the spirit of Ron Edwards (he is not dead as of my writing this, but I very much hope not to summon actual Ron Edwards here to serve me a pedantic rant about terminology). We need to talk about the Shared Imagined Space.

The Shared Imagined Space is a thing that does not exist. Like many things that do not exist (such as a "reasonable person" or the number 3) it is nevertheless an important and useful concept that has important implications for important things that people do. In this case, playing RPGs

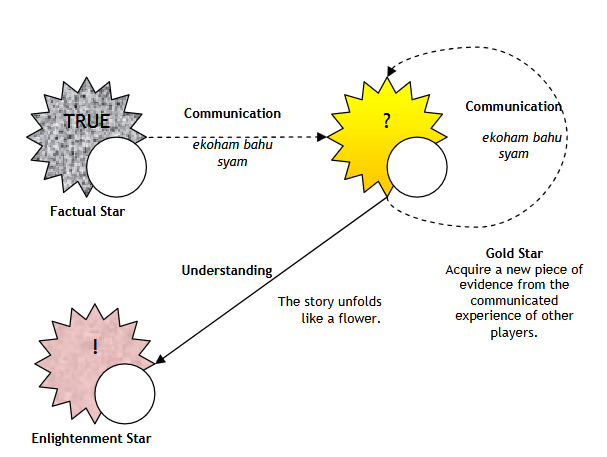

I am not going to recap the minutiae of Forge theory here - go read Hegel or something instead - but the important thing to understand about the shared imagined space (SIS) is that it is "all of what the players mutually agree happens in a role-playing game." The SIS contains everything that happens on-screen; it's a combination of contributions by all of the players to describe events and people that exist within the experience of play. It doesn't include things that are off-screen; players may be under completely different impressions about things that have not been instantiated into the game. Or they might not! But either way, the sphere of the SIS gradually expands over time as the world is revealed. Jenna Moran's Wisher Theurgist Fatalist diagrams the process quite well:

Hope that clarifies things.

One of the big problems with the SIS, fundamentally, is that time exists. Well, that time goes forwards. We need a way to add elements to the SIS that doesn't feel like random asspulls. Previous discourse has resulted in redefining the word "system" to fit this process, and I believe this is in large part because defining the word "system" was arguably the primary project of the Forge. Per Vince Baker,

However you and your friends, moment to moment, establish and agree to what's happening in your game, that's your game's system.

Let's leave this here for now and jump tracks.

The main idea of Rules Elide, as a TTRPG design and analysis ideology (that has long since departed from the narrow scope of the blogpost linked above), is that rules, system, design, incentives - whatever you want to call the whole superstructure of the engine that facilitates the interactions of different things on various pieces of paper - often numbers, but checkboxes and short answer fields work too - that thing is Not The Point. That thing is a fiction-reduction machine that sucks all the life out of the vibrant shared imagined space and turns it into a procedural and contextless bucket of undifferentiated paste. This is not necessarily believed to be a bad thing - abstraction is sometimes necessary - but it is believed that subjecting the stuff your RPG is about to excessive abstraction sucks the life out of it.

Various extensions of the argument move this core idea in slightly different directions - some people would say that the major sin of rules-forward design is that it deprioritizes the integrity of the fictional world, or that rules are an attempt to claim credit for the creativity of players. But I think that these are pretty fundamentally similar takes. The basic premise is that rules force players to contort themselves into weird little shapes in order to follow their dreams.

Finally, I will return to what I said above - in the abstract, this is not always taken to be a bad thing. Jared's original blogpost says,

We use rules to remove some of the trees, so we might better see the forest.

The fundamental argument of this position isn't about whether rules are good or bad, or even about what rules do, emotionally. It's about how rules structure play. I happen to like play that's at least moderately structured by rules, but I'm not writing about how the rules elide people are having badwrongfun. I'm writing about how I think rules structure play, and how I disagree with them.

In Forge terms, system is a thing you have, and also a thing you do. It's an artifact that presents affordances to its players on how they can evolve the shared imagined space, but it's also the metaphysical sum of all of the processes by which that evolution occurs. If this sounds internally contradictory and a bit incoherent, I think that's fair. That's why I'm talking about rules, not systems. But like, also, they're fundamentally similar.

Rules are a thing that you have. Sometimes they're a thing you make, but you do have them. In more rulings-based or fiction-forward systems, many of the resolution mechanisms may not be written rules, but they do imitate rules that exist. X-in-6 is a very typical resolution mechanism for uncodified scenarios in OSR type games, while the Blades in the Dark SRD provides a breakdown of potential consequences for rolls that's both flexible enough to cover most scenarios and rich enough with examples that it sets expectations outside of those bounds. In both of these cases, examples are key. By providing examples, you (the game designer) can provide the players with the context they need to make reasonable inferences about how to play the game.

By providing text on character sheets (and in the rulebook), you provide the players with the context they need to make reasonable inferences about what their characters can do.

The shared imagined space, like I said, isn't real. The "mutual agreement about what happens" is a patchwork, a set of discrete points in the space and time of the fiction where one specific result is observed. Players extrapolate the rest of the fiction from these points. Most often, the gaps are filled by the real world. Sometimes, they're filled in with the players' imaginations. These can diverge wildly.

Athletics (80%) tells us several things about the game. Not just the rules, but how the game plays. It tells us that this character is an athletic kind of person, and hopefully provides us with enough examples that we can understand what sort of athletics an Athletics (80%) character can expect to accomplish. It tells us that obstacles in this game can meaningfully be addressed by feats of athleticism. It tells us that we can expect other characters in the fictional world to employ athletics when appropriate. It tells us that you can fail at athletics, even though you're good at it, and that we can hang stakes on your athletic ability that are narratively interesting on both ends. The cost of these convenient features is that you lose the ability to define your athleticism with authorial power within the SIS.

Keeping on the subject of athletics, let's see how that tradeoff plays out. "But I lift" is a meaningful objection to you when your character fails at carrying a sack of potatoes because your failure to effectively employ your character's athleticism in a rules interaction causes friction with your internal fiction. If you've brought that fiction before the table convincingly, it may even cause friction with the SIS. But, unironically, this is a skill issue. You have not interpreted the thing on your character sheet correctly.

"OK," I can hear you say, "but why should what's on my character sheet matter so much?"

Part of the reason to play whatever game you are playing in this imagined example is, presumably, that you accept the twin premises that aleatory failure is structurally interesting and that it is structurally possible, for you, specifically. If you are portraying a character whose mechanics outcomes are incompatible with their fictional portrayal, you are rejecting the SIS that the other players share. Just because you understand real-world bodybuilding better than the author of the game you are playing doesn't mean that it's appropriate, in a playing-an-RPG-facilitating sense, to deny the premises that the rest of the people at the table are playing under. The abstraction created by the rules doesn't just function to abrogate detail, it calibrates how everyone thinks the action being abstracted works It doesn't only remove detail - it adds clarity. The SIS, may not exist, but these layers of abstraction are still crucial to its uh... non-existent coherence.

It's OK to prefer RPGs that are more or less mechanized, in terms of who gets to decide what about what. It's okay to use the skeleton of an RPG that you're going to extensively redefine and house-rule until it's closer to freeform than not. Personally, I don't think anything is inherently lost or gained thereby. A lot of the ink spilled on and adjacent to this topic has been on the subject of whether or how rules help or hinder people having fun (or feeling like they can be expressive, or instantiate their fantasies). Frankly, I don't care.

Whether you want to be a dirt farmer who randomly dies off the back of a bad roll on the infectious disease table in GURPS or a shapeshifting assassin horse-robot in steampunk Mongolia in FATE or a wandering pacifist philosopher-revolutionary in heavily houseruled Dungeons and Dragons, I think you probably have a good reason to play the game you are playing. But I think that making sure you are all playing the same game is an obligation we have to each other. Clashing expectations is the source of... well, maybe not most table drama in general, but certainly most table drama I've been a part of or adjacent to. The important takeaway here, for me, is that if your table doesn't agree on what the rules you're playing by are or mean, you are failing to maintain the shared imagined space, and you should probably consider that other players are probably not expecting you to challenge their understanding of how conflict resolution works in the fiction that you are all kind-of-sharing. Make a new rule, make a new plan, whatever. But please, try to make sure you're all on the same page.

Did you like this post? Tell us

Leave a comment

Log in with your itch.io account to leave a comment.