TeachQuest was a project I was involved in from March 2023 to March 2024 as a game design researcher. The goal of the project was to deliver a game that could communicate teaching to STEM undergraduates and inform them about a career in teaching. In this short postmortem, I will highlight the design of TeachQuest, the user research conducted, and the challenges that arose.

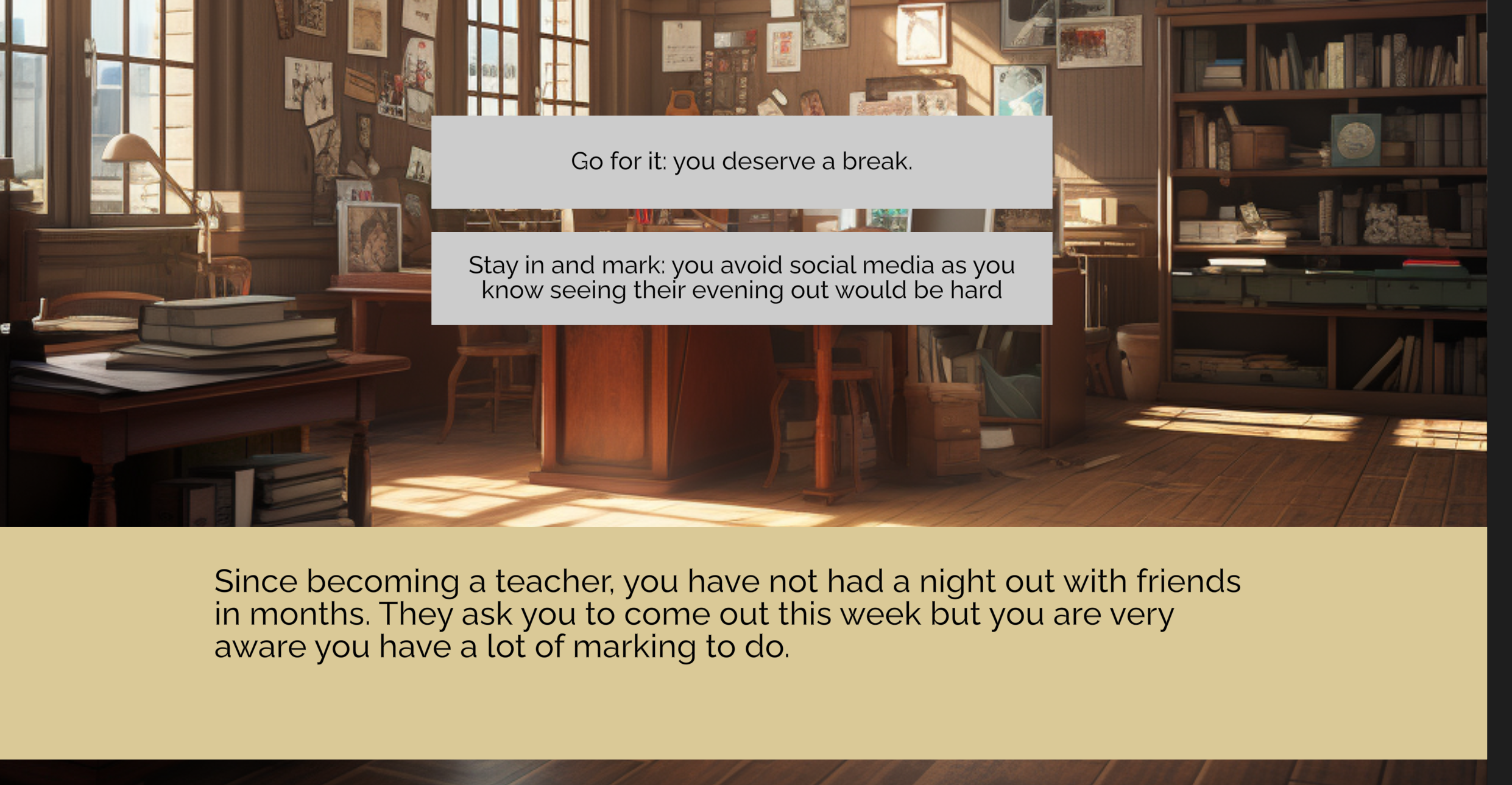

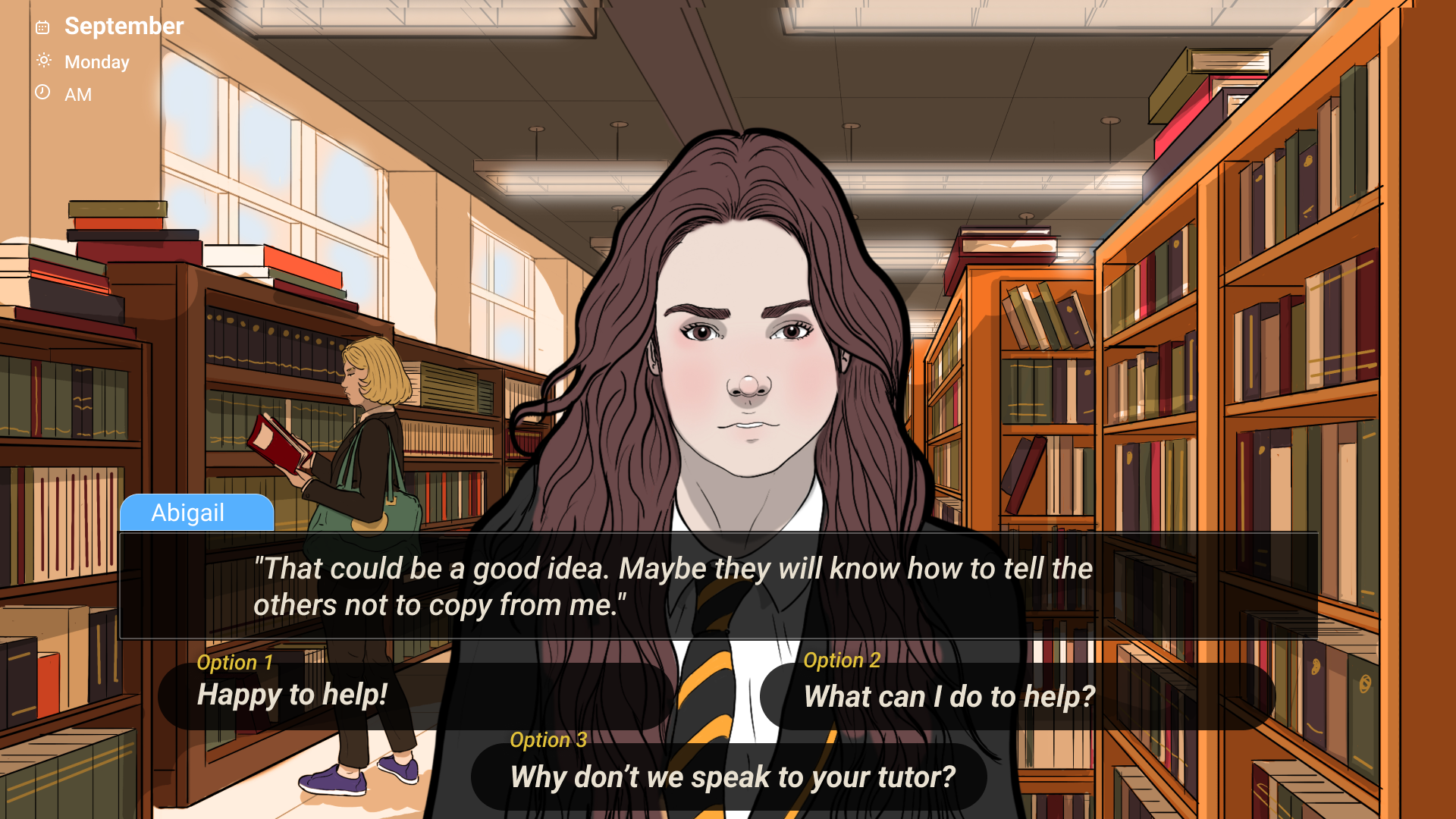

TeachQuest is a short narrative game where you play as a science teacher in a fictional secondary school (Loxley High) set in Sheffield, UK North. Through a series of scenarios, you are given multiple branching choices and narratives which impact characters' stories and the feedback you receive from your mentor. TeachQuest was designed with Teachers to provide content based on real teacher anecdotes, portraying the difficult decisions they make, as well as some of the more humorous incidents that can occur.

You can play a demo of TeachQuest here: https://mikethingsbetter.itch.io/teachquest or at www.playteachquest.com

Initial Design

The project had a scope of 12 months to design, test and deliver a game that could inform and potentially persuade STEM undergraduates aged 18-25 to consider a career in teaching. At the beginning of the project, I researched similar games that aimed to communicate to players or portray teaching. Games such as Uber Game, Spent, Reigns, Game Director, and Growing Up made up a shortlist of games within scope. In particular, Uber Drive and Spent convey narratives with complex and interesting choices, very much similar to the “choose your own adventure” games or books. These games all involve simple intuitive controls, with simple buttons and gesture controls which appeal to non-gamers. The duration of these games is relatively short too, roughly between 10-20 minutes, meaning players can usually finish a playthrough in one sitting without losing their attention.

Uber Game pictured above by The Financial Times

With this prior research in mind, we proposed a visual novel concept with branching choices. We created a paper prototype (read more about that here), which was a deck of cards to emulate screens of a mobile device. A bit ‘theatre of the mind’ was used to give feedback and responses to players. The results of playtesting the paper prototype of TeachQuest were quite positive, the format and genre suited our target audience, with a desire for more content and more agency in their decisions.

Iterations and User Testing

Following the paper prototype, we developed the card system into javascript in the Playcanvas engine. The browser based engine allowed for collaborative working and could export projects to browser for mobile or desktop devices. The digital prototype made use of additional transitions where we could now have more complex dialogue, back and forth between characters, and change characters in and out of scenes. We utilised temporary AI artwork at this phase as we had not hired our artist yet and we knew that ‘rougher’ prototypes can often result in distracting feedback from playtesters. We recruited 13 playtesters for this version of our prototype, conducting 1-to-1 stimulated recall tests where participants played the game as we observed their behaviour and interactions with TeachQuest.

The results of our initial testing highlighted a mechanic involving the dissemination of teaching information that was not of interest to players, they found them boring and rarely chose those options in favour of character events. However, we did find the content curated with teachers was authentic to our target audience, where they believed these events could take place. However, the main feedback we received was around the lack of context and consequences. The design and narrative of TeachQuest did not provide players with enough context on what their goal was and who some characters were concerning their character.

With this feedback in mind, we had hired an artist and writer to add polish to the game. From the paper prototype and first round of user research, we had established an art style our core audience were interested in. To address the narrative and text, we refined the dialogue to provide more context and background to each scenario that the player encountered. Together with drafts of new artwork, we recruited 12 participants to test whether TeachQuest was (1) Fun (2) accessible to our target audience (3) Gave enough direction and context and (4) raised their interest in teaching. We conducted the same 1-to-1 testing with each participant and asked the majority of participants to play the game on their mobile devices.

Early concept of Artwork and layout for TeachQuest

Through this round of user testing, participants were well informed of context and goal, but we learned there were too many transitions and too much text for them to digest. Participants weren’t interested in reading text with nothing else on-screen (such as characters or maps). Players really enjoyed the sense of agency with choices, as we had changed the number of choices from 2 to 3 and they really enjoyed how the map screen (pictured below) gave them freedom to choose who they help and speak to. These choices were also a lot harder to players which created much more meaningful and interesting choices. This round of user testing also highlighted technical challenges on devices, where we needed to revisit the layout and text size to ensure an accessible and readable text to mobile devices. What was also concerning was also how long TeachQuest took to complete. We had added too much text and scenarios, where the game had previously taken 20 minutes, it now took 45 minutes, with some players churning out before then.

We had to revisit the text and really cut down on what information we gave to the player. During this point in development, we were creating the dialogue and text in Ink, a narrative engine, which our developer tied into Playcanvas. Ink gave us a much more usable writing space where we could add variables and tag characters with identifiers compared to working inside a script. We introduced an initial scene to provide introduction to key characters as a way of providing context to players and we implemented variables throughout the random events and scenarios to check if a player met a character before. These variables would be able to provide core context to characters or events but avoid repetition between scenarios or playthroughs. In addition, we also used these variables to create a ‘banter’ system between characters. The banter system was described by Inkle Studios Jon Ingold at Develop Brighton 2023 keynote, where providing quips or interjections by characters helps remove the repetition in narrative games. Given we designed a random ‘deck’ of scenarios which could appear in any order, we implemented variables to change dialogue between characters based on other events that could have taken place.

The iteration of this phase were quite substantial but we were nearly 9 months into our 12 month deadline. We implemented as much as we could and created two different builds, one shorter and more concise text, one with more detail and text. We repeated our previous user study design and analysed the results, learning that the shorter structure worked better. Including rich descriptions or context setting was not particularly interesting to our participant group, instead favouring the choices they were presented and the consequences they presented. The feedback from this phase of development was overall, much more positive. We now knew how much text our audience were interested in and we had thoroughly tested the variety of scenarios and narratives the player would encounter. Players had expressed concerns at some scenarios and narratives that we were able to refine or remove after discussion with education specialists. What was gratifying to see was the change in feedback across the user research studies where we saw initial concerns for believability amended by later feedback.

Final product

In the remaining 3 months we focused on delivering the academic goals of the project, fixing bugs, and implementing more branching choices in TeachQuest. We added the remainder of backgrounds produced by our artist and hired a composer to create UI and background sounds. Throughout development we had designed a number of scenarios and characters that could not all possibly fit into a 20 minute experience so we build a number of versions of TeachQuest.

With the huge amount of content, we also made a second term for the full game, where players could continue playing after half term and handle their students getting excited from festive breaks, but also worrying about exams.

Given our scope of 12 months, I believe the design of TeachQuest may have overshot what it intended to deliver. We managed to create a game that was fun to our target audience and could infer what motivates our audience to consider teaching. However, we did create too much content that most players will not see and character assets that aren’t regularly used. Instead, that time could have been better spent on creating characters with multiple emotions as was originally planned.

When it came to the overall user research of TeachQuest, I believe the steps we took to test with our audience was the only reason for its success. If we had not have tested regularly with our audience, our text, scenarios and artwork may not have interested or engaged our target audience. In addition, I don’t think we would have created a believable or honest representation of teaching without the education teams involvement and feedback from our audience.

Did you like this post? Tell us

Leave a comment

Log in with your itch.io account to leave a comment.